Summary of the Research Proposal

The aim of this research project is to provide a critical historical analysis of the Asia Minor campaign of 1919-1922 through the study of the wartime trauma and its impact on the Greek soldiers who participated in the war. To this end the scope of the research will be twofold: The first part will reconstruct the multifarious painful experiences of the Greek troops in Asia Minor, whereas the second will focus on the rehabilitation and social reintegration challenges these war veterans faced in Greece throughout the interwar period.

The Greek-Turkish war proved to be a severe traumatic experience with numerous and intense physical and emotional challenges for the Greek soldiers. The first section of the proposed research will focus on the soldiers’ subjective experiences and based on their narratives will examine their physical and emotional reactions. To this end it will trace their psychological changes as these were conditioned by weariness, alienation, homesickness, the concern about their families’ wellbeing and the loss of their brothers-in- arms. It will also present the consequences of the soldiers’ exposure to state coercion, adverse conditions, illnesses, captivity and violent death, while at the same time approach the issue of the inevitable dehumanization of a significant portion of them, which transformed them into perpetrators or bystanders of ethnic violence and war crimes.

The experience of the war did not end with the termination of hostilities and demobilization, but accompanied many veterans throughout their lives. The healthcare, rehabilitation and social integration of the ex-servicemen, both able-bodied and disabled, constituted one of the major challenges of the interwar period. One of the objectives of this research is to investigate how the state apparatus – and partly private initiative – undertook the healthcare of this new social category. In this context, it will examine the various attitudes formed within the veterans’ circle with regards to the effectiveness of the welfare mechanisms developed in order to address this issue. At the same time, it will attempt to bring to the foreground the image of the “veteran” as this was shaped in the public discourse of the time – veteran publications, protest letters, press articles, literature, photographs and memorial events – by placing special emphasis on the family, social and economic impact of the physical and psychological trauma. The project will draw material from a wide array of primary sources, published material of the period and secondary bibliography.

Workshop

Friday 23 April 2021

Greek Soldiers, War and Trauma: The Asia Minor Campaign and the Consequences of a Painful Experience

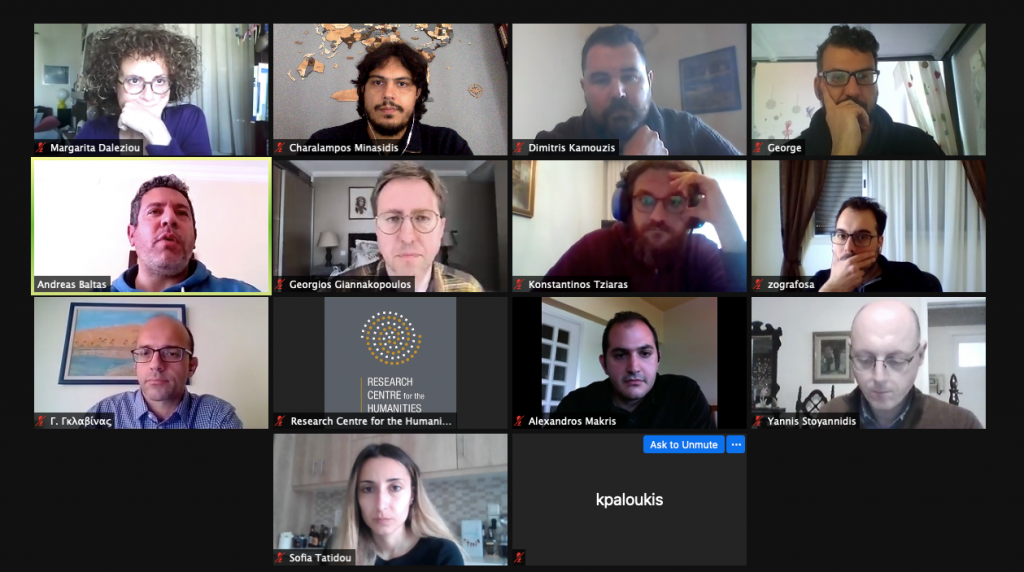

The closed online workshop of our group entitled “Greek Soldiers, War and Trauma: The Asia Minor Campaign and the Consequences of a Painful Experience” took place on Friday 23 April 2021 at the RCH platform.

The purpose of the workshop was to prepare the open conference planned for November 2021.

The meeting was attended by the researchers of RCH, Dimitris Kamouzis, Alexandros Makris and Charalambos Minasidis; the RCH administrator Despoina Valatsou; and our colleagues George Giannakopoulos (King’s College London), Yannis Glavinas (General State Archives), Margarita Daleziou (University of the Aegean), Anastasios Zografos (University of Cyprus), Andreas Baltas (Panteion University), Kostas Paloukis (Historical Archive Thessaloniki Port Authority), Giannis Stoyiannidis (University of West Attica), Sofia Tatidou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki), Kostas G. Tziaras (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki) and Giorgos Chraniotis (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki).

The meeting lasted for 8 hours and we had a fruitful discussion on various aspects of the issue such as:

– Violence and war perceptions

– Recruitment and volunteering

– Psychological, physical and mental challenges during the war

– Daily life on the front

– Politicization and radicalism

– Resistance, desertion and disobedience

– Prisoners, victims and missing persons of war

– Rehabilitation, union organization and social reintegration in Greece during the interwar period

– War, masculinity and gender relations

– Trauma and memory

The final texts of the workshop and the November conference will be published in a collective volume (in Greek) by the Publications “Vivliopoleion tis Estias” in 2022.

Research: “Greek Soldiers, War and Trauma: The Asia Minor Campaign and the Consequences of a Painful Experience”

Researcher: Dimitris Kamouzis, Charalampos Minasidis, Alexandros Makris

The research project “Greek Soldiers, War and Trauma: The Asia Minor Campaign and the Consequences of a Painful Experience” was funded by the Research Centre for the Humanities (RCH) for the year 2021.

Introduction

The main object of this research project was to study the multifarious painful experiences of the Greek troops in Asia Minor, the impact of the wartime trauma and the rehabilitation and social reintegration challenges these war veterans faced in Greece throughout the interwar years. One should not forget that out of the approximately 450,000 soldiers who served during the war period 1912-1922 (Balkan Wars, World War I and the Asia Minor Campaign), close to 200,000 fought in the Greek-Turkish War (1919-1922).[1] From several viewpoints (economic, social, political, labor, etc.) these veterans, along with the refugees who arrived in Greece following the ‘Asia Minor Catastrophe’ of 1922, constituted the two main pillars of Greek society after the war.

The novelty of this research lies in the fact that the study of war as experienced, remembered and expressed by the soldiers themselves, but also by those who were eyewitnesses, continues to be a completely marginalized historiographical issue in Greece, especially in comparison with the relevant international literature. As George Th. Mavrogordatos correctly points out, contrary to the Greek case the official research centers working on the history of war abroad do not employ only military experts for their projects, but also include historians and other social scientists. He adds that military history is an extremely problematic field of investigation and recording, as it is characterized by ‘an inescapable injustice: the testimonies of the men who fell in battle are missing.’[2] But what about the testimonies of those who survived the Asia Minor Campaign? And what other sources remain untapped in domestic historical research?

The response to these questions forms the core of the program’s broader ambition, which is to become the starting point for a more general and multifaceted discussion on the study of the Asia Minor Campaign as a ‘history from below’ and its contextualization according to the social and political conditions of that specific era. To this end, the members of the research team invited other scholars working on different aspects of the issue to present their findings at two online events, a closed workshop (23 April 2021) and an open conference (12 November 2021) that were hosted by the Research Center for the Humanities (RCH).

The collective volume entitled Greek Soldiers and the Asia Minor Campaign: Aspects of a Painful Experience that emerged from these fruitful discussions and will be published in Greek within 2022[3] aims at providing a critical historical analysis of the traumatic war experience and the short- and long-term effects on the Greek soldiers who participated in the Greek-Turkish War in alignment with the contemporary historiographical trends on the ‘Great’ or ‘Greater War.’[4] The topics examined in the forthcoming book are violence and war perceptions; recruitment and volunteering; resistance, desertion and disobedience; masculinity and gender relations; psychological, physical and mental challenges; daily life on the front; prisoners, missing persons and victims of war; politicization and radicalism; diseases and disability; veterans’ rehabilitation, union organization and social reintegration; and trauma and memory. The relevant chapters of Dimitris Kamouzis (in collaboration with Giorgos Giannakopoulos), Alexandros Makris and Charalampos Minasidis discussed briefly below, were produced within the framework of the program funded by the RCH.

The presence of the Greek Army in Asia Minor: The perspective of the British ‘eyewitnesses’

The focal point of Kamouzis’ sub-project was to highlight critical aspects of the British attitude towards the Greek military involvement in Asia Minor through the analysis of the information provided by ‘eyewitnesses,’ in this case the on-the-spot reports of British observers –army officers, diplomats, intellectuals and special envoys–, the findings of the inter-allied commissions of inquiry set up after the violent conduct of the Greek army against the Muslim populations in the province of Aydin and in Kios, Yalova and Nicomedia, the discussions in the British Parliament and the political and journalistic discourse of the period.

The facts that led to the deployment of Greek forces in Smyrna in May 1919 and the violent events that followed are more or less known. On the other hand, largely unknown remain the British views and perceptions in relation to the peacekeeping role of the Greek army in the region, which had served as a pretext for the Greek landing in the first place. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George as well as his coalition government supported the campaign in Asia Minor and Greek geopolitical aspirations, placing them within the more general framework of Great Britain’s colonial policy and its effort to secure by proxy the Eastern Mediterranean,[5] a vital region for the preservation of its financial, commercial and strategic interests. [6] However, as early as 1919 the Asia Minor Campaign became a subject of internal political controversy in Britain, both inside and outside government circles, with technocrats, politicians and diplomats expressing serious reservations about the viability of the Greek intervention.

These reservations were based not only on strategic, but also on cultural arguments, which were linked to the growing weakness –at least in the eyes of the Western allies– of the Greek forces, and therefore of Greece, to appear worthy of the ‘cultural mission’ they had undertaken. The ensuing Greek-Turkish War sparked a vicious cycle of violence and retaliations against civilians, both Turks and Greeks, which included looting, massacres, rapes, destruction and arson. The reaction of the Great Powers was the formation of ad hoc committees with the task of detailing and investigating incidents of violence exercised by both sides. The committees and the findings they produced were moving on parallel axes. A common component was the view that the Greeks and their military presence in Asia Minor exacerbated the situation and brought to the surface ‘eternal’ passions and rivalries. In other words, the Greek troops were not able to accomplish any ‘peacekeeping’ or ‘cultural’ mission in the region, even if they claimed otherwise.

Certainly, this rather one-dimensional view, where violence and hatred were perceived as ‘natural’, ‘primordial’ and ‘eternal’, ignored the particular political and historical conditions on the ground that had facilitated a period of ethnic violence and revenge in Asia Minor from the Balkan Wars onwards. In any case the uncontrollable escalation of the war, the empowerment of the Turkish nationalists in military, political and diplomatic terms and the wave of humanitarian sympathy in Britain regarding the atrocities committed against the Muslim population by the Greek army as well as paramilitary groups, resulted in the gradual alteration of British policy towards Greece. At the same time, the unnecessary violent events in the province of Aydin in the summer of 1919 and in Yalova, Kios and Nicomedia in the spring of 1921 challenged a common and long-lasting Western ideological place of analysis and interpretation of the Eastern Question that always treated the Christian populations as victims of persecution and never as perpetrators.

The report of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry into the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjacent Territories

The conduct of the Greek army in the summer of 1919[7] had created a climate of intense pressure on the government of Lloyd George,[8] which was reinforced by the report of the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry into the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjacent Territories discussed at the Paris Peace Conference on November 8 of the same year.[9] Of particular interest was the second part of the report entitled ‘Establishment of Responsibilities,’ which essentially reflected the concerns of British observers regarding the actions of the Greeks during the first months of the Greek occupation.[10] At the outset the report argued that since the Armistice of Mudros (30 October 1918) the general situation of the Christians in the vilayet (prefecture) of Aydin had been satisfactory and their safety had not been menaced (Point 1).[11] Therefore, the committee disputed the original argument invoked by the Big Three (Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and US President Woodrow Wilson) to justify the order of the occupation of Smyrna by the Greek army.[12] According to the inquiry, the Greeks had done nothing to prevent the ‘religious hatred,’ which had been the initial cause of these events. Their occupation, far from appearing like the execution of a civilizing mission, had immediately assumed the form of ‘a conquest and a crusade’ (Point 2). Furthermore, the exact cause of the tragic events that took place in the Meander Valley was the advance of the Greek troops and the unjustified occupation. However, the responsibility was not only of the Greeks. At this point the commission reiterated the argument of ‘the hatred which had existed for centuries’ between Turks and Greeks that had escalated the frequency and brutality of the violence.[13]

The conclusions presented by the commission, which formed the third part of the report, left no doubts about the effects of the presence of the Greek army in Asia Minor and the measures that had to be taken.[14] According to their findings, the situation that had been created in Smyrna and in the vilayet of Aydin had taken a wrong turn, because the occupation, which in principle aimed only at the maintenance of order, presented in reality all the forms of annexation and was incompatible with the return of order and peace necessary for the well-being of the populations in the region. In addition, it imposed considerable military sacrifices on Greece, which were out of proportion to the mission to be accomplished.[15] The commission therefore recommended that all or part of the Greek troops be replaced as soon as possible by a smaller allied army, which practically meant the end of the Greek occupation and Greece’s claims in Asia Minor. At the same time, however, its suggestions offered a unique opportunity to the Greek government to disengage from Asia Minor with the least possible cost to Greece and minimum damage to the prestige of the Allies.[16]

Venizelos, recognizing that such a decision would deliver a severe blow to the Greek irredentist policy of the Megali Idea (Great Idea), refuted the suggestions of the committee.[17] The recommendations of the report were also detrimental to the interests of the Allies –particularly the British– as no country intended to replace the Greek army with its own troops in Asia Minor. The shared opinion was that the Greeks were still the ideal and only available force to deal with the growing Turkish nationalist movement in the region. As a result, the report of the Allied Inquiry Commission was kept secret.[18] On two different occasions, in March 1920 and in May 1922, the opposition in Great Britain tried in vain to put pressure on the government of Lloyd George to bring the report to the House of Commons for discussion.[19] The full report was finally made public for the first time –by the Americans, not the British– in 1946, twenty-seven years after it was formally submitted at the Paris Peace Conference.[20] This fact alone is telling of the importance attached to it, especially after the tragic outcome of the Asia Minor campaign in 1922.

Reports on the Atrocities in the Districts of Yalova, Guemlek and the Ismid Peninsula

In the spring of 1921, the Allies agreed to set up two new inter-allied commissions similar to the one of 1919. One would investigate the violent incidents of Kios (Guemlek) and Yalova and the other those of Nicomedia (Ismid).[21] According to the reports of these committees, the atrocities that took place during the movement of the Greek army at the end of March 1921 could be considered as the consequences of war retaliations, but this was not the case for the unprovoked arson of villages and the destruction that had taken place on the northern shore of the Gulf of Mudania.[22] On the contrary, in a way reminiscent of the Carnegie Commission’s findings on the Balkan Wars,[23] they interpreted violence as the result of the ‘age-long hatred existing between the various races.’ They argued that these passions were fuelled by the presence of thousands of Armenian and Greek refugees in the area with fresh memories of the persecutions and atrocities committed against them by the Young Turks.[24]

The overall conclusion of the reports was that the atrocities that took place against Christians on the one hand, and Muslims on the other, were unworthy of a civilized government, whether these were areas occupied by the Greek troops or controlled by the Kemalists.[25] And if ‘Turkish barbarism’ was taken for granted by most of the Allies, it was the Greek government that was losing in the eyes of these commissions the privilege of a ‘civilized’ entity, a force that was expected to ensure peace and order in Asia Minor.[26]

In the autumn of 1921, Britain’s official attitude towards Greece began to shift due to the wide exposure of the violence of the Greek army in English newspapers and the impasses of British policy in the Near East.[27] The defeat of the Greek forces and the ‘Asia Minor Catastrophe’ of 1922 practically marked the end of British support to the Greek presence in Asia Minor and was essentially the swan song of Lloyd George’s government. During the course of events the British Prime Minister had ignored on several occasions the reports, warnings and advice of his experts against the continuation of the Asia Minor Campaign considering them biased and pro-Turk. In the election campaign that followed in October 1922, he tried in vain to restore Gladstone’s legacy with constant references to the moral obligation of protecting the Christian populations of the East. In the end the failure of the Greek army to impose the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres on the Turkish nationalists brought the collapse of Lloyd George’s pro-Greek policy in Asia Minor dragging him down in its fall.

The Asia Minor Campaign and the mobilization of the local Greek Orthodox population

The Asia Minor Campaign proved to be a traumatic experience with many intense physical and psychological challenges for the local Greek Orthodox population. It revealed the limits of the Megali Idea, but also the will of the Greek Orthodox to mobilize for its implementation and, then, its protection. After all, they were the victims of its failed outcome. Minasidis’ contribution to the research project focuses on the Greek Orthodox, would-be Greek citizen soldiers, who mobilized either alongside the Greek armed forces or paramilitary groups. It also examines those who evaded the draft or deserted, in order to analyze the attitude of the Greek Orthodox male population as a whole towards the new war. Following an approach ‘from below,’ it is mainly based on the testimonies of the Ottoman Greeks themselves. It examines the empirical data using the concepts of continuous negotiation between the citizen soldier and the state,[28] cultural (re)mobilization or demobilization and the cultures of war that include them,[29] war weariness[30] and the war contract, part of the economy of sacrifice.[31]

This sub-chapter argues that the attitude of the Greek Orthodox during the Asia Minor Campaign was a result of personal will, specific circumstances and economy. It was influenced by a variety of factors such as their political and national consciousness; their militant anti-Turkish radicalization, or the lack of it; their hitherto negative experiences; their perception of war; their personal and family situation and the fluidity of male role models in the midst of war; their frustration due to the escalation of the war; the weaknesses of the Greek military presence; the political changes in Greece; the international environment and the absence of a welfare state; and finally the social control and state enforcement, or the lack of both. The sub-chapter claims that the mobilization of most Ottoman Greeks was under constant negotiation. In this light, alternative mobilizations such as those of boy scouts, militias and other paramilitaries, even women, suggest the emergence of different notions of masculinity and cultures of violence, the belief that war was an open process conducted under different forms, and demonstrate that despite the wave of desertions and draft evasions among the ranks of Ottoman Greek soldiers, 1922 marked the total mobilization of the Asia Minor community.

Complacency, indifference and military fugitiveness

The challenges of the Ottoman Long War (1911-1923) and the belief of many Greek Orthodox that the war was over, influenced their attitude towards the prospect of their armed participation under the Greek banner. The successive wars had interrupted everyone’s life, cost countless lives, and led to the impoverishment and refugeedom of their families, most of whom had been deprived of their main breadwinners. The return of refugees, deportees, draft evaders, deserters and recently demobilized from the Ottoman armed forces was accompanied by their realization that the destruction and abandonment of their properties during the war or their occupation by Balkan Muslim refugees jeopardized their survival and economic recovery. Simultaneously, the Greek military presence and the inclusion in the Greek culture of victory[32] had convinced most Greek Orthodox that their military mobilization was unnecessary since the Greek armed forces had liberated them and offered them a false illusion of security. Therefore, the participation in the Greek culture of victory, combined with a sense of war weariness and the urgent need to prioritize individual and family interests, initially turned most Greek Orthodox to complacency and cultural demobilization.

The Greek Orthodox population gradually began to understand that complacency was contrived, that the war was not over, and that they had to abandon their plans to return to a peaceful life. Their gradual mobilization began, without being offered a war contract. The Greek state did not establish welfare mechanisms for the protection and survival of their families, during their absence, while it promised them only demobilization after the final victory. The gradual mobilization also conveyed to the population the weaknesses and vague goals of Greek policy, which, from a possible mandate in Smyrna, ended up waging an unwanted total war,[33] without being clear whether the areas outside the Smyrna zone would be united with Greece after the war, and thus if it was worth the sacrifice of Asia Minor Greeks. These negative impressions were reinforced by the post-November 1920 political and international changes.[34] For many Ottoman Greeks all of the above displayed insecurity, caused disillusionment, and possibly futility, and led to draft evasion and desertion.[35]

Due to war weariness, the continuation of the war was not also sufficiently justified in ideological terms for many Orthodox Greeks. Several of them either had not constructed a Greek national consciousness or a militant anti-Ottoman attitude, while others remained nationally indifferent, denied their Greek citizenship, if they held one, or Greek ethnicity and claimed to be foreign or Ottoman citizens.[36] However, the survival of many Greek Orthodox communities in the Greek zone automatically meant the preservation of the social fabric and therefore of social ties and societal control. Even if the local young men did not want to enlist under the Greek banner or deserted, their local community intervened and forced them, either directly or indirectly, in accordance with the manly standards of the time, to consent with their mobilization.[37]

Volunteers, conscripts and war cultures

The volunteers had developed the will and motivation to enlist, even though they were not Greek citizens. Most of them considered the Greek-Turkish war as an opportunity for the liberation and unification of their home territories with Greece. They combined a concrete Greek political and national consciousness, a militant anti-Ottoman stance and the acceptance of their possible sacrifice. For those who were, themselves or their families, victims of the Young Turks’ anti-minority and genocidal policies and of Muslim paramilitary violence, participating in the Greek Army’s operations was seen as an opportunity for resistance and revenge. Their voluntarism offered highly motivated and pro-war soldiers, who had no problem (re)mobilizing, as well as soldiers seeking an adventure, knowledgeable about the local terrain and networks, and of the Turkish language. Their service could also accelerate the demobilization of older classes.

Simultaneously, their service was crucial from a symbolic point of view as it homogenized the drafted nation and functioned as yet another legitimizing factor for the war service of the Greeks from the Greek Kingdom, reminding them that the Great Idea had not been fully realized as long as parts of the nation remained still unredeemed. Concurrently, the voluntary service of Asia Minor Greeks identified their interests with those of the Greek state and functioned as an element of legitimacy for the Greek mandate in the zone of Smyrna, the Greek military presence in Western Asia Minor and its future annexation with Greece, while the service of the Pontic and Constantinopolitan Greeks maintained these national questions open, without ruling out a future military intervention. All of the above advocated for the emergence of volunteers as an important category of soldiers with multi-purpose and symbolic functions.[38] However, many Greek Orthodox were also mobilized as recruited volunteers, as the escalation of the war, the strengthening of the Turkish national movement and the fear of the return of the Young Turks led the Greek authorities to draft all available able-bodied men and convinced many Asia Minor Greeks that their war service was essential.[39]

Alternative mobilizations

Nevertheless, the inability of the Greek Army to protect all Greek Orthodox communities from the Muslim paramilitary violence[40] and Greek Orthodox paramilitaries’ successes[41] convinced many Greek Orthodox that in order to protect their communities more effectively, they had to join paramilitary groups, instead of conventional military units. The changes that occurred after the Armistice of Mudros offered the opportunity to many Greek Orthodox to self-mobilize by openly organizing their own militias, but also to retaliate against and plunder Muslim communities.[42] As a result, new paramilitary elites emerged, whose socialization with the culture and norms of violence, made them more extremist and less willing to recognize the traditional communal hierarchy and its usually compromising attitude.[43] Soon, these paramilitary bands increased in such a degree that offered their services to the Greek Army, and acquiring the role of disciplining, terrorizing and exterminating the local alien or enemy population. This model seems to have worked as long as there was no widespread uprising of Muslim peasants until the final retreat of the Greek army and the simultaneous appearance of Turkish military units.[44] In 1922, in the context of the total mobilization of the Asia Minor Greek society, National Defense militias formed in many communities,[45] while the urgent need for the general mobilization of the local friendly population led to the establishment of the Asia Minor Militia under the authority of the Greek armed forces.[46]

Another alternative mobilization was that of the student youth. In the newly liberated territories, 83 groups of boy scouts –and 45 in Constantinople– were established for the purpose of the youths’ military training. The boy scouts were constructing the New Greek citizen soldier and therefore emerged as a key element in the integration of the youth of the new territories into the Greek drafted nation. During the war, they were mobilized as a paramilitary corps to assist the Greek armed forces, to boost the morale of their communities, and to act as mouthpieces of the Great Idea at the local level. In fact, it was the only public and openly accepted by the Greek state paramilitary corps throughout the war period.[47]

War and memory: The public image of veterans in interwar Greece

In the aftermath of the Asia Minor Campaign and the demobilization, war veterans emerged as a new social category in Greek society. Makris’ research tried to reconstitute the public image of these veterans in interwar Greece in order to comprehend the social impact of war by focusing mainly on three dimensions: a) the self-image of veterans, b) their place in war memory, and c) the depiction of them in interwar literature.

The self-image of ex-servicemen can be reconstructed by their ego-documents (memoirs, veterans’ newspapers, articles on daily press etc.). These sources provide details for aspects of the war, like trauma or personal thoughts of the combatants, which the political and military histories often overlook. A first common memory was the veterans’ dreadful appearance in the immediate aftermath of their demobilization.[48] This memory was stronger to former prisoners of war, who were released gradually between 1923 and 1924.[49] Another constant complaint was about the state welfare for the former fighters and their families, which was considered insufficient. This grievance was a common reference especially for some categories of veterans like disabled and people who suffered from tuberculosis.[50] The wide and multi-dimensional welfare system for veterans, initiated during the war period and expanded in the interwar years,[51] was considered by many ex-servicemen as limited. However, we should generally bear in mind that regardless of how generous a welfare system is, the veterans will not stop demanding for more.[52] To sum up, the self-image of former fighters during the interwar period was characterized by two main traits: a) their adverse situation, especially in the aftermath of their homecoming, and b) the perception that the insufficient state welfare was the main reason for this situation.

As regards war memory, this sub-chapter examined it on two levels in order to reconstruct more efficiently the veterans’ public image: a) the position of ex-servicemen in official war memory, b) the conceptualization of the war and especially the Asia Minor Campaign in the individual memory of the veterans. The official memory was constructed by the state. Despite the defeat of 1922, the Greek Army was victorious for nine years (1912-1921), therefore a culture of victory was cultivated in Greek society from the Balkan Wars onwards. After a significant setback in the mid-1920s (as a consequence of the Asia Minor defeat), this ‘hybrid culture of victory’ (based on the theoretical approaches of Wolfgang Schivielbush and John Horne) continued to develop in Greece especially in the 1930s.[53]

By and large, veterans played a secondary role in this process. It should be pointed out that between 1922 and 1925, its early phase, the Greek veterans’ movement was linked with the Communist Party of Greece. During this period the movement expressed a hard antimilitarist line and organized militant agrarian demonstrations in 1925. This attitude led the state to crush the veterans’ movement and this policy facilitated a relationship of suspicion between the state and ex-servicemen, which lasted until the early 1930s.[54] This fact explains the veterans’ absence from the formation of war memory. However, the situation gradually changed from the late 1920s onwards, when the state accepted their (loyal) associations and veterans abandoned their communist past. In the second interwar decade, veterans participated in various rituals of war commemoration, like monument unveilings, most significant of which was undoubtedly the Monument of the Unknown Soldier in Athens (1932), parades and national or local commemorations. They gradually gained an honorary status in ceremonies, not only those related to the war memory, but also in religious celebrations or commemorations of older events of Greek history like the Greek Revolution. Thus, they became an organic component of the Greek ‘hybrid culture of victory.’[55]

On the subject of individual memory, ego-documents allow us to delve into the personal opinions of the former soldiers. A common feature was the pride for the achievements of the Greek Army in Anatolia since most of their memoirs included relevant comments.[56] However, the debacle of August 1922 was perceived in various ways. Some blamed the Great Powers or the Antivenizelist governments, others the fanaticism provoked by the National Schism, and some tried to explain what happened through the viewpoint of Greek imperialist aspirations or the political Left.[57] But in general, all agreed that the Greek soldier was not responsible for the defeat. Moreover, additional negative memories were the proximity with death, the atrocities against civilians (arson, looting, rapes etc.) during the campaign[58] and the experience of captivity.

A competitive memory critical to the war was expressed by the communist Left, especially by the Federation of Ex-Soldiers and Military Victims, which albeit short-lived (1924-1925) was the biggest veterans’ organization during the interwar period. Despite the Federations’ strong influence, this war memory was marginal and expressed only by communist circles.[59] Even memoirs of veterans who participated in communist-orientated Unions of Ex-Soldiers, which used a hard anti-militaristic rhetoric, referred with pride to their participation in the Asia Minor Campaign.[60] Overall, it could be argued that individual war memory brought to the surface many negative aspects of the Greek-Turkish War. However, these aspects did not diminish the pride of the men who participated in it. The individual memory largely agreed with the ‘hybrid culture of victory’ regarding the meaning of war during the interwar period.

The third pillar of this research was literature. Although it does not offer direct historical information, books authored by writers who lived during a specific historical period (in our case the interwar years), provide various information regarding the social image of a historical subject.[61] From this perspective, references to veterans in novels and poems can contribute to the reconstruction of their image in the public sphere. By and large, war literature flourished in the aftermath of the First World War expressing mainly a strong anti-war stance. Emblematic examples were Le feu (Under fire) written by Henri Barbusse (1916), Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front) by Erich Maria Remarque (1929) and the dramatic play Journey’s End by R.C. Sheriff (1928). In Greece, the ‘Generation of the ’30s,’ a group of writers who had experienced the war decade, depicted in their works the social impact of the Asia Minor Campaign. A noteworthy dimension of this impact was undoubtedly that of the ex-servicemen.

The most typical example of a veteran-writer was Stratis Myrivilis, whose book Η δασκάλα με τα χρυσά μάτια (The school teacher with the golden eyes, 1933) portrays numerous aspects of the social reintegration of a veteran into a post-war society.[62] Firstly, the protagonist, who felt in love with the spouse of his killed comrade, had a clearly anti-war attitude,[63] like the vast majority of Greek war veterans. Secondly, there are many references to the rightful claim of veterans, widows and war orphans for a decent welfare system.[64] These references illustrate an international change of attitude towards veterans, which derived from the Great War.[65] Thirdly, in the book one can trace various phases of the Greek veterans’ movement of the early interwar period like the communist orientated associations of ex-servicemen and the agrarian demonstrations for land distribution to veterans.[66]

The literary mentions to ex-servicemen derived not only from veteran-writers, but generally from well-known authors of the interwar period (e.g. Giorgos Theotokas, I.M. Panagiotopoulos, Thanasis Petsalis-Diomidis).[67] Furthermore, the negative aspects of the war, like the mass deaths as well as the limited welfare protection of ex-servicemen and war victims were also at the epicentre of many poems. Angelos Sikelianos, Georgios Athanasiasis-Novas, Markos Tsirimokos, Stefanos Morfis and Maria Zamba were some of the poets who highlighted the social marginalization of the veterans as well as the mass mourning for the fallen.[68] Moreover, some journals of the Left, which had a critical attitude to wars, like Neoi Vomoi, published stories with veterans as protagonists in order to emphasize the piteous situation of the former heroic fighters.[69] The literature depiction of veterans had many common characteristics with their self-image. The social marginalization and the negative dimensions of war experience were ubiquitous. An additional trait was that, in contrast to what happened with the refugees, whose stories were mainly authored by refugee-writers,[70] the references on the former soldiers did not come exclusively from veteran-writers.

To conclude, the presence of veterans in interwar public discourse was notable as it becomes apparent by their texts, their memory practices and the relevant literature. The attempt to reconstruct their public image led to a dual condition. The social marginalization was a constant characteristic in their ego-documents and in literary works especially in relation to invalids, former prisoners and veterans who suffered from diseases like tuberculosis. But simultaneously, the positive conceptualization of the Asia Minor Campaign and the central position gradually obtained by the veterans in war memory gave a heroic meaning to their presence in the public sphere. As a result, during the interwar period veterans were caught between social marginalization and their heroic past.

Bibliography

Archives

Benaki Museum Historical Archive (HABM)

Eleftherios Venizelos Archives

Petimezas Family Archive

Centre for Asia Minor Studies (CAMS)

Oral Tradition Archive (ΟΤΑ)

Manuscripts Archive

Department of State,

Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1921, v. II, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 1936.

Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference 1919, Volume IX, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1946

Diplomatic and Historical Archives of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Central Service Archive

The National Archives (TNA), Foreign Office (FO)

UK Parliament, House of Commons Hansard

Books & Articles

Alexandris, Alexis (ed.), Το αρχείον του εθνομάρτυρος Σμύρνης Χρυσοστόμου όπως διεσώθη από τον μητροπολίτη Αυστρίας Χρυσόστομο Τσίτερ, v. III, Μικρά Ασία, Μητροπολίτης Σμύρνης, Β΄, 1918-1922, National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation, Athens 2000.

Allamani, Efi and Panagiotopoulou, Krista, ‘Η συμμαχική εντολή για την κατάληψη της Σμύρνης και η δραστηριοποίηση της ελληνικής ηγεσίας. (Συμπλήρωμα στο Ημερολόγιο του Ε. Βενιζέλου 6-19 Μαΐου 1919)’ in Thanos Veremis and Odysseas Dimitrakopoulos (eds.), Μελετήματα γύρω από τον Βενιζέλο και την εποχή του, Ekdoseis Philippoti, Athens 1980, pp. 119-172.

Ανθολογία της νεοελληνικής γραμματείας. Η ποίηση, vol. III, Iraklis, Renos, Irkos and Stantis Apostolidis (eds.), Ta Nea Ellinika, Athens 2011.

Apostolidis, Petros, Όσα θυμάμαι 1900-1969, 2 vol., Kedros, Athens 1981 and 1983.

Argiropoulos, Petros D., Έζησα… 11 μήνες αιχμάλωτος στους Τούρκους, Alexandra Politostathi (ed.), Athens 1999.

Aslanoğlu, Anna Maria, Staying away from Politics, not Foreseeing Militarism: The Case of Corps of Greek Scouts in Armistice Istanbul, 1918-1923, Master thesis, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul 2010.

Athanas, G. [Georgios Athanasiadis-Novas], Καιρός πολέμου, Sideris, Athens [1924].

Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane and Becker, Annette, 14-18: Understanding the Great War, trans. Catherine Temerson, Hill and Wang, New York 2002.

Axiotis, Manolis, Εγώ, ο Μανώλης Αξιώτης… Η περιπετειώδης ζωή του ήρωα των “Ματωμένων Χωμάτων”, Baltas Publishing Company, Vartholomio Ilias 2016.

Benlisoy, Foti, Kahranmanlar, Kurbanlar, Direnişçiler: Milli Mücadele’de Yunan Ordusu’nda Komünist Propaganda, Grev ve İsyan (1919-1922), İstos Yayın, İstanbul 2019.

Beşikçi, Mehmet, The Ottoman Mobilization of Manpower in the First World War: Between Voluntarism and Resistance, Brill, Leiden 2012.

Buzanski, Peter M., ‘The Interallied Investigation of the Greek Invasion of Smyrna, 1919,’ The Historian 25/3 (1963), pp.325-343.

Cabanes, Bruno, The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2014.

Chouzouri, Elena, Η στρατιωτική ζωή στη Νεοελληνική Λογοτεχνία, Epikentro, Athens 2020.

Cornelissen, Christoph and Arndt Weinrich (eds.), Writing the Great War: The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present, Berghahn, London 2020.

Coutau-Bégarie, Hérvé, ‘Seapower in the Mediterranean from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century’ in John B. Hattendorf (ed.), Naval Policy and Strategy in the Mediterranean: Past, Present, Future, Frank Cass Publishers, Oxon 2000, pp. 30-48.

Crotty, Martin, Neil J. Diamant and Mark Edele, The Politics of Veteran Benefits in the Twentieth Century. A Comparative History, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, ΝΥ-London 2020.

Daleziou, Eleftheria, Britain and the Greek-Turkish War and Settlement of 1919-1923: The pursuit of security ‘by proxy’ in Western Asia Minor, unpublished PhD thesis, Department of History, University of Glasgow, Glasgow 2002.

Diamantopoulos, Vasilis G., Αιχμάλωτος των Τούρκων (1922-23), Athens 1977.

Exarchos, Giorgis (ed.), Ενθύμιον Στρατού, Ermis-Kronos, [Athens] 1987.

Genikon Epiteleion Stratou, Επίτομος Ιστορία Εκστρατείας Μικράς Ασίας 1919-1922, Ekdosis Dieythinseos Istorias Stratou, Athens 1967.

Gennimatas Vasilios, ‘Το τελευταίον έτος εις Μ. Ασίαν’, Macedonia (25 May-28 August 1930).

Gerwarth, Robert and John Horne (eds.), War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2012.

Gerwarth, Robert and Erez Manela (eds.), Empires at War, 1911-1923, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014.

Glafiros, Mpampis, ‘Αρντιζ-Νταγ’, Rizospastis (27 July 1933).

Horne, John, ‘Demobilizing the Mind: France and the Legacy of the Great War, 1919-1939’, French History and Civilization 2 (2009), pp. 101-119.

Horne, John, ‘The living’ in Jay Winter (ed.), The Cambridge History of the First World War, vol. III, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2014, pp. 592-617.

Indian Khilafat Delegation, Atrocities Committed by the Greeks in Smyrna. Report of the Commission of Inquiry, appointed by the Supreme Council of the Allies, concerning the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjacent Territories; dated Constantinople, the 12th October, 1919. The Indian Khilafat Delegation, Publications. No. 5, Bonner and Co., London (no date).

Kafetzaki, Tonia, Προσφυγιά και λογοτεχνία. Εικόνες του Μικρασιάτη πρόσφυγα στη μεσοπολεμική πεζογραφία, Poreia, Athens 2003.

Kamouzis, Dimitris, Greeks in Turkey: Elite Nationalism and Minority Politics in Late Ottoman and Early Republican Istanbul, Routledge, London and New York, 2021.

Dimitris Kamouzis and Giorgos Giannakopoulos, ‘“Η σοφία της τοποθέτησης των Ελλήνων στη Σμύρνη -και πιο πέρα- αποδεικνύεται καθημερινά και βαθύτερη:” Βρετανικές (α)πόψεις της παρουσίας του ελληνικού στρατού στη Μικρά Ασία’ in Dimitris Kamouzis, Alexandros Makris and Charalampos Minasidis (eds.), Έλληνες στρατιώτες και Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία. Πτυχές μια οδυνηρής εμπειρίας, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 2022 (forthcoming).

Karagiannis, Christos, Το ημερολόγιον του Χρήστου Καραγιάννη 1918-1922, [Athens 1976].

Katiforis, N.G., ‘Για μια καινούργια Ανάσταση’, Neoi Vomoi 5 (May 1924), pp. 131-141 and 6 (June 1924), pp. 170-180.

Kostopoulos, Tasos, Πόλεμος και Εθνοκάθαρση: Η Ξεχασμένη Πλευρά μιας Δεκαετούς Εθνικής Εξόρμησης 1919-1922, Vivliorama, Athens 2008.

Krause, Jonathan (ed.), The Greater War: Other Combatants and Other Fronts, 1914-1918, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire 2014.

Leed, Eric J., No Man’s Land: Combat and Identity in World War I, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1979.

Lemonidou, Elli, Ιστορία και μνήμη του Α΄ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου στην Ευρώπη, Papazisis, Athens 2019.

Llewellyn-Smith, Michael, Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor 1919-1922, Hurst & Co., London 1998.

Liris, K., ‘Πίσω! Πίσω!’, Rizospastis (28 August 1934).

Louis, G., “Τσαούς-Τσιφλίκ”, Rizospastis (13 and 14 August 1933).

Makris, Alexandros, ‘Οι κήρυκες της ιδέας του έθνους.’ Παλαιοί πολεμιστές, ανάπηροι και θύματα πολέμου στην Ελλάδα (1912-1940), Unpublished PhD Thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens 2021.

Mavrogordatos, Giorgos Th., ‘Χρήση και κατάχρηση της στρατιωτικής ιστορίας,’ I Kathimerini (28 July 2020).

Michalopoulos, Fanis, ‘Τρεις νύχτες’, Νeoi Vomoi 4 (April 1924), pp. 97-106.

Morfis Stefanos, ‘Αιχμαλώτων γυρισμός,’ Noumas 774 (May 1923), p. 329.

Myrivilis, Stratis, Η δασκάλα με τα χρυσά μάτια, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 2018.

Naltsas, Christoforos, ‘Η εκστρατεία της Μ. Ασίας’, Macedonia (26 January-8 May 1930).

Nikas, P., Το βιβλίο του φαντάρου, Alexandreia 1925.

Ntampos, Konstantinos, Μικρά Ασία 1914-1922. Το χρονολόγιο του ανθυπασπιστή Κωνσταντίνου Ντάμπου, Giannis Makridakis (ed.), Pelinnaio, Chios 2005.

Orfanos, Philippos [Pantelis Pouliopoulos], Πόλεμος κατά του Πολέμου. Αποφάσεις του Πρώτου Πανελληνίου Συνεδρίου Παλαιών Πολεμιστών και Θυμάτων Στρατού, Diathnis Vivliothiki, Athens 2008 (1st ed. 1924).

Panagiotopoulos, I.M., Αστροφεγγιά. Η ιστορία μιας εφηβείας, Astir, Athens 1980.

Paradeisis, Nikolaos K., Ο προσκοπισμός στις αλησμόνητες πατρίδες, 1919-1922: Μικρά Ασία, Κωνσταντινούπολη, Θράκη, O Mikros Romios, Athens 2000.

Petsalis-Diomidis, Thanasis, Δεκατρία χρόνια, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 1977.

Priniotakis, Pantelis, Ατομικόν ημερολόγιον. Μικρά Ασία, 1919-1922, N.A. Kavvadias (ed.), Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 1998.

Report of the International Commission to Enquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan War, Carnegie Endowment of International Peace, Washington, D.C. 1914.

Reports on Atrocities in the Districts of Yalova and Guemlek and the Ismid Peninsula, His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London 1921.

Romvos, Teos and Mintilou (eds.) Γεώργιος Κηπιώτης: Ένας φίλος των παιδιών, Digital Edition, 2016, <https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BwIu1Dtxi2X3Rmp4LUk2YzN2NjQ/view? resourcekey=0-6b3ku4 IMzHntkFJXmWHkOQ>.

Sanborn, Joshua A., Drafting the Russian Nation: Military Conscription, Total War and Mass Politics, 1905-1925, Northern Illinois University Press, De Kalb, IL 2003.

Smith, Leonard V., Between Mutiny and Obedience: The Case of the French Fifth Infantry Division during World War I, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1994.

Spanomanolis, Christos A., Αιχμάλωτοι των Τούρκων, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 1969.

Tekir, Süleyman and Ural, Selçuk, ‘Batı Anadolu’da Yunan İşgali ve Aydın Muhacirleri (1919-1920)’ Cumhuriyet Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi, 13/26 (2017), pp. 125-148.

Theodoridis, Ant., ‘Το τέλος του Ταξιδιού’, Macedonia (31 August 1930).

Theotokas, Giorgos, Αργώ, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 2016.

Toynbee, Arnold Joseph, The Western Question in Greece and Turkey, Constable and Company Ltd., London 1922.

Tsaprazlis, Kostas, Απ’ τη Δομνίστα στο Κάλε Γκρότο και πάλι πίσω (αναμνήσεις από τον Πόλεμο της Μ. Ασίας), Ath. Stamatis (ed.), Filoproodos Sillogos Domnistas, Athens 1990.

Tsirimokos, Markos, Ώρες του δειλινού, Athens 1930.

Tzanakaris, Vasilis I., Σμύρνη 1919-1922: Αριστείδης Στεργιάδης εναντίον Χρυσοστόμου, Metaihmio, Athens 2019.

Wyrtzen, Jonathan, Worldmaking in the Long Great War: How Local and Colonial Struggles Shaped the Modern Middle East, Columbia University Press, New York 2022.

Varnava, Andrekos, British Cyprus and the Long Great War, 1914-1925: Empire, Loyalties and Democratic Deficit, Routledge, London and New York 2020.

Zampa, Maria, Τα τραγούδια μου, Athens 1924.

[1] Genikon Epiteleion Stratou, Επίτομος Ιστορία Εκστρατείας Μικράς Ασίας 1919-1922, Ekdosis Dieythinseos Istorias Stratou, Athens 1967, p. 140. For the overall number of the men who fought during the period 1912-1922 see Alexandros Makris, ‘Οι κήρυκες της ιδέας του έθνους.’ Παλαιοί πολεμιστές, ανάπηροι και θύματα πολέμου στην Ελλάδα (1912-1940), Unpublished PhD Thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens 2021, pp. 312-314.

[2] Giorgos Th. Mavrogordatos, ‘Χρήση και κατάχρηση της στρατιωτικής ιστορίας,’ I Kathimerini (28 July 2020).

[3] The volume will be published by the Publications ‘Vivliopoleion tis Estias.’

[4] For the historiography of World War I see Elli Lemonidou, Ιστορία και μνήμη του Α΄ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου στην Ευρώπη, Papazisis, Athens 2019; Christoph Cornelissen and Arndt Weinrich (eds.), Writing the Great War: The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present, Berghahn, London 2020. The concept of the ‘Greater War’ expands chronologically and territorially the study of the Great War by including in it all the conflicts and fronts between 1911 and 1923. Indicatively see Robert Gerwarth and John Horne (eds.), War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2012; Robert Gerwarth and Erez Manela (eds.), Empires at War, 1911-1923, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014; Jonathan Krause (ed.), The Greater War: Other Combatants and Other Fronts, 1914-1918, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire 2014. Respectively, the schema of the ‘Long Great War’ focuses on the conflicts and the social, economic and political developments that were a direct consequence of the Great War. See Andrekos Varnava, British Cyprus and the Long Great War, 1914-1925: Empire, Loyalties and Democratic Deficit, Routledge, London and New York 2020; Jonathan Wyrtzen, Worldmaking in the Long Great War: How Local and Colonial Struggles Shaped the Modern Middle East, Columbia University Press, New York 2022.

[5] For an excellent analysis of this approach see Eleftheria Daleziou, Britain and the Greek-Turkish War and Settlement of 1919-1923: The pursuit of security ‘by proxy’ in Western Asia Minor, unpublished PhD thesis, Department of History, University of Glasgow, Glasgow 2002.

[6] Hérvé Coutau-Bégarie, ‘Seapower in the Mediterranean from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century’ in John B. Hattendorf (ed.), Naval Policy and Strategy in the Mediterranean: Past, Present, Future, Frank Cass Publishers, Oxon 2000, p. 43.

[7] Apart from the cases of Smyrna and Aydin anarchy, violent ethnic conflicts and extremism by Greek and Turkish forces -regular and paramilitary- against Turks and Greeks respectively continued that summer in various areas such as Menemen, Pergamos, Değirmencik, Karabunar, Nazilli, Alaşehir (Philadelphia), Papazli, Yeni Çiflik, Soma, Akhisar, Usak, Magnesia, Agiasmati, Bursa and Söke (Sokia). For detailed British accounts of these events see the following dossier: The National Archives (henceforth TΝΑ), Foreign Office (henceforth FO) 608/90.

[8] Only in the period June-August 1919 the issue had officially been brought for discussion in the British parliament six times. UK Parliament, House of Commons Hansard: Smyrna (Alleged Greek Massacres), Volume 116, debated on Wednesday 4 June 1919, Column 1997, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-06-04/debates/08ab55b8-ead7-4087-b4c7-8464507ead96/Smyrna(AllegedGreekMassacres); Smyrna (Greek Massacre), Volume 117, debated on Thursday 26 June 1919, Column 304, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-06-26/debates/6be8150f-973f-4626-8088-bb8303b4fba5/Smyrna(GreekMassacre) ; Greece (Conditions in Smyrna), Volume 117, debated on Thursday 3 July 1919, Column 1134, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-07-03/debates/cfdaa15e-c8ea-4f73-85e4-24330fd8a498/Greece(ConditionsInSmyrna) ; Smyrna and Aidin (Massacres), Volume 118, debated on Thursday 24 July 1919, Column 1532, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-07-24/debates/b193e894-e378-44d4-ab9d-60f2d2d88a27/SmyrnaAndAidin(Massacres) ; Asia Minor (Greek Action), Volume 118, debated on Tuesday 29 July 1919, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-07-29/debates/84b69478-3bf7-4097-b321-17de49896d67/AsiaMinor(GreekAction) ; Asia Minor (Greek Action), Volume 119, debated on Monday 4 August 1919,https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-08-04/debates/fdb33c19-3372-4f6a-8635-22841b5f795b/AsiaMinor(Massacres) (last access 2 September 2021).

[9] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference 1919, Volume IX, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1946, pp. 45-46; Peter M. Buzanski, ‘The Interallied Investigation of the Greek Invasion of Smyrna, 1919,’ The Historian 25/3 (1963), pp. 328-330. The complete report and the minutes of the discussion of that day are also available online here: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1919Parisv09/d3 (last access 2 September 2021).

[10] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, pp. 68-70. The first part, entitled ‘Statement of the Facts’ was essentially a review of the events that followed the landing of the Greek army in Smyrna, incorporating some of the findings of the independent report that had been prepared on 28 July 1919 by the Greek colonel Alexandros Mazarakis-Ainian. For Mazarakis-Ainian’s report see Historical Archives of the Benaki Museum (henceforth HABM), Eleftherios Venizelos Archives, 018/44.

[11] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, p. 68.

[12] After just five days of discussions, during which Lloyd George repeatedly supported the occupation of Smyrna by Greek troops in order to protect the local Greek population, the leaders of Britain, France and the United States decided on 6 May 1919 the immediate dispatch of Greek army in the area. For detailed accounts of the events that led to the decision of the Big Three and the violent incidents that followed the Greek landing see Michael Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor 1919-1922, Hurst & Co., London 1998, pp. 77-91; Efi Allamani and Krista Panagiotopoulou, ‘Η συμμαχική εντολή για την κατάληψη της Σμύρνης και η δραστηριοποίηση της ελληνικής ηγεσίας. (Συμπλήρωμα στο Ημερολόγιο του Ε. Βενιζέλου 6-19 Μαΐου 1919)’ in Thanos Veremis and Odysseas Dimitrakopoulos (eds.), Μελετήματα γύρω από τον Βενιζέλο και την εποχή του, Ekdoseis Philippoti, Athens 1980, pp. 119-172.

[13] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, pp. 69-70.

[14] Ibid., pp. 71-73.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, pp. 112-113.

[17] Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, pp. 113-115; Buzanski, ‘The Interallied Investigation,’ p. 334. For the overall attitude of the Greek government towards the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry see Diplomatic and Historical Archives of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Central Service Archive, 1919, 0/0, Α5VI 9: Smyrna Commission of Inquiry.

[18] Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision, p. 114; Buzanski, ‘The Interallied Investigation,’ pp. 341-342.

[19] UK Parliament, House of Commons Hansard: Smyrna (Massacres), Volume 126, debated on Monday 15 March 1920, Columns 1806-1807, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1920-03-15/debates/aeaea505-6186-4721-92d5-44c8557373a3/Smyrna(Massacres); UK Parliament, House of Commons Hansard: Official Commission (Report), Volume 127, debated on Monday 22 March 1920, Columns 28-29, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1920-03-22/debates/f52f2aa5-70d8-47cc-9d44-901e1c465d8a/OfficialCommisson(Report); UK Parliament, House of Commons Hansard: Smyrna (Atrocities Commission), Volume 154, debated on Wednesday 24 May 1922, Column 1206, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1922-05-24/debates/78514b86-2474-4da0-b179-3567060eb7c3/Smyrna(AtrocitiesCommission); Smyrna (Alleged Atrocities), Volume 154: debated on Thursday 25 May 1922, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1922-05-25/debates/df926b0b-cbfc-42bf-80cb-1bcc98b88b34/Smyrna(AllegedAtrocities) (last access 2 September 2021).

[20] See Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Volume IX. At the time there were some unofficial propaganda leaflets published with parts of the report. See for example: Indian Khilafat Delegation, Atrocities Committed by the Greeks in Smyrna. Report of the Commission of Inquiry, appointed by the Supreme Council of the Allies, concerning the Greek Occupation of Smyrna and Adjacent Territories; dated Constantinople, the 12th October, 1919. The Indian Khilafat Delegation, Publications. No. 5, Bonner and Co., London (no date).

[21] Turkey No1 (1921). Cmd. 1478. Reports on Atrocities in the Districts of Yalova and Guemlek and the Ismid Peninsula, His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London 1921.

[22] Ibid., p.4

[23] See Report of the International Commission to Enquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan War, Carnegie Endowment of International Peace, Washington D.C. 1914.

[24] Reports on Atrocities, p.4.

[25] Ibid., p.5.

[26] Cf. Tasos Kostopoulos, Πόλεμος και εθνοκάθαρση. Η ξεχασμένη πλευρά μιας δεκαετούς εθνικής εξόρμησης (1912-1922), Vivliorama, Athens 2007, pp. 114-123.

[27] See for example ‘Greek Massacre of Moslems,’ Manchester Guardian (27 May 1921); ‘Unsettling the Near East,’ The Manchester Guardian (26 October 1921).

[28] See Leonard V. Smith, Between Mutiny and Obedience: The Case of the French Fifth Infantry Division during World War I, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1994.

[29] See Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Annette Becker, 14-18: Understanding the Great War, trans. Catherine Temerson, Hill and Wang, New York 2002; John Horne, ‘Demobilizing the Mind: France and the Legacy of the Great War, 1919-1939,’ French History and Civilization 2 (2009), pp. 101–119.

[30] See Benjamin Ziemann, War Experiences in Rural Germany, 1914-1923, trans. Alex Skinner, Berg, Oxford 2007, pp. 7-8, 73-110, 182-184, 241-242.

[31] See Eric J. Leed, No Man’s Land: Combat and Identity in World War I, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1979; Joshua A. Sanborn, Drafting the Russian Nation: Military Conscription, Total War and Mass Politics, 1905-1925, Northern Illinois University Press, De Kalb, IL 2003; Mehmet Beşikçi, The Ottoman Mobilization of Manpower in the First World War: Between Voluntarism and Resistance, Brill, Leiden 2012.

[32] See Alexis Alexandris (ed.), Το αρχείον του εθνομάρτυρος Σμύρνης Χρυσοστόμου όπως διεσώθη από τον μητροπολίτη Αυστρίας Χρυσόστομο Τσίτερ, v. III, Μικρά Ασία, Μητροπολίτης Σμύρνης, Β΄, 1918-1922, National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation, Athens 2000, p. 48; Dimitris Kamouzis, Greeks in Turkey: Elite Nationalism and Minority Politics in Late Ottoman and Early Republican Istanbul, Routledge, London and New York, 2021, pp. 45-73.

[33] See Dimitris Kamouzis and Giorgos Giannakopoulos, ‘“Η σοφία της τοποθέτησης των Ελλήνων στη Σμύρνη -και πιο πέρα- αποδεικνύεται καθημερινά και βαθύτερη:” Βρετανικές (α)πόψεις της παρουσίας του ελληνικού στρατού στη Μικρά Ασία’ in Dimitris Kamouzis, Alexandros Makris and Charalampos Minasidis (eds.), Έλληνες στρατιώτες και Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία. Πτυχές μια οδυνηρής εμπειρίας, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 2022 (forthcoming).

[34] Indicative of the sense of urgency and feeling abandonment by the Allies are the articles in the Smyrna newspapers Kosmos and Synadelfos.

[35] The Centre for Asia Minor Studies (henceforth CAMS) holds several testimonies by Greek Orthodox draft evaders.

[36] See Foti Benlisoy, Kahranmanlar, Kurbanlar, Direnişçiler: Milli Mücadele’de Yunan Ordusu’nda Komünist Propaganda, Grev ve İsyan (1919-1922), İstos Yayın, İstanbul 2019, pp. 152-157; 868.117/112, The High Commissioner at Constantinople (Bristol) to the Secretary of State, 353, 18 July 1921 in The Department of State, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1921, v. II, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 1936, p. 173.

[37] See Manolis Axiotis, Εγώ, ο Μανώλης Αξιώτης…: Η περιπετειώδης ζωή του ήρωα των “Ματωμένων Χωμάτων,” Baltas Publishers, Vartholomio Ilias 2016, pp. 182-185.

[38] On their motives, see CAMS, Oral Tradition Archive (henceforth OTA), Lydia: Axari, Konstantinos Mpaltas (September 27, 1968); Lydia: Axari, Αιχμαλωσία: Konstantinos Mpaltas (27 September 1968); CAMS, Manuscripts Archive (henceforth MA), Dimitrios Symvonis, Έτος 1919-1970: Βιογραφία, April 15, 1970, pp. 3-4, 70.

[39] CAMS holds numerous testimonies by volunteers and recruited volunteers alike.

[40] See CAMS, OTA, Aeolia: Magnesia, Η ελληνική κατοχή του 1922: Evangelos Karampetsos, March 24, 1962.

[41] See CAMS, OTA, Aeolia: Magnesia, Τον καιρό της Κατοχής του 1919: Evangelos Karampetsos, March 24, 1962; CAMS, OTA, Aeolia: Papazli, Magnesia, Smyrna, Η κατάληψη του Παπαζλί το 1919: Olympia Souvantzi, March 16, 1962; Aeolia: Papazli, Magnesia, Η αντίσταση του Παπαζλί το 1919: Evangelia Gaki, September 24, 1962; Aeolia: Papazli, Magnesia, Αναμνήσεις από την κατοχή του Παπαζλί το 1919: Anastasios Samiotis, June 23, 1962; CAMS, OTA, Aeolia: Karagatsli, Magnesia, Τον καιρό της Κατοχής του 1919: Antonis Sarmoutsos, March 19, 1963.

[42] See Ryan Gingeras, Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1912–1923, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2009, pp. 69-70; Vasilis I. Tzanakaris, Σμύρνη 1919-1922: Αριστείδης Στεργιάδης εναντίον Χρυσοστόμου, Metaihmio, Athens 2019, p. 271.

[43] See Axiotis, Εγώ, ο Μανώλης Αξιώτης, pp. 62-63, 89-98, 114, 162, 165-166, 191-192, 196; CAMS, OTA, Aeolia: Pergamos, Ο Μουφτής του Κεμερίου: Theodoros Kampouris or Ntikos, February 18, 1964; CAMS, MA, Evangelos Chatziioannou, Αυτοβιογραφία, Xanthi, 1962, pp. 2, 21-22; Arnold Joseph Toynbee, The Western Question in Greece and Turkey, Constable and Company Ltd., London 1922, pp. 107-113, 120-121, 294; Kostopoulos, Πόλεμος και Εθνοκάθαρση, pp. 114-123; Kamouzis and Giannakopoulos, ‘“Η σοφία της τοποθέτησης.”’

[44] According to Turkish documents of the period, the fear and panic created by several Greek paramilitary groups resulted in the weakening of the Turkish resistance and local Muslim economic activity and the exodus of the Muslim population to non-Greek occupied areas, see Süleyman Tekir and Selçuk Ural, ‘Batı Anadolu’da Yunan İşgali ve Aydın Muhacirleri (1919-1920)’ Cumhuriyet Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi, 13/26 (2017), pp. 125-148.

[45] For instance, Michail Konstantinou, born in 1877, stated that ‘[d]uring the Greek occupation, he was in the National Defense and had 35 gunmen under his orders,’ see CAMS, OTA, Lydia: Philadelphia, Michael Orologas, February 29, 1968. Konstantinou in Greece was renamed Orologas.

[46] HABM, Petimezas Family Archive, Introduction Number 241, Konstantinos Pet[i]mezas, Asia Minor Militia 1921-1922.

[47] See Teos Romvos and Mintilou (ed.) Γεώργιος Κηπιώτης: Ένας φίλος των παιδιών, Digital Edition, 2016, <https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BwIu1Dtxi2X3Rmp4LUk2YzN2NjQ/view?resourcekey=0-6b3ku4IMzHntkFJXmWHkOQ>, pp. 141-142; CAMS, OTA, Aeolia: Chamidie, Magnesia, Smyrna, Σχέσεις Ελλήνων και Τούρκων: Christos Kalaïtzopoulos, December 5, 1961; Nikolaos K. Paradeisis, Ο προσκοπισμός στις αλησμόνητες πατρίδες, 1919-1922: Μικρά Ασία, Κωνσταντινούπολη, Θράκη, O Mikros Romios, Athens 2000, p. 84; Anna Maria Aslanoğlu, Staying away from Politics, not Foreseeing Militarism: The Case of Corps of Greek Scouts in Armistice Istanbul, 1918-1923, Master thesis, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul 2010, p. 94.

[48] For example see Kostas Tsaprazlis, Απ’ τη Δομνίστα στο Κάλε Γκρότο και πάλι πίσω (αναμνήσεις από τον Πόλεμο της Μ. Ασίας), Ath. Stamatis (ed.), Filoproodos Sillogos Domnistas, Athens 1990, p. 83.

[49] Indicatively see Christos A. Spanomanolis, Αιχμάλωτοι των Τούρκων, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 1969, pp. 275-276; Petros D. Argiropoulos, Έζησα… 11 μήνες αιχμάλωτος στους Τούρκους, Alexandra Politostathi (ed.), Athens 1999, pp. 50-54.

[50] For example see reports of relevant demonstrations at the veterans’ newspapers Drasis (12 April 1923); Anapiriki Foni (24 June 1928); Panefedriki (7 June 1936). For references about the limited protection in veterans’ memoirs see Christos Karagiannis, Το ημερολόγιον του Χρήστου Καραγιάννη 1918-1922, [Athens 1976], p. 361; Petros Apostolidis, Όσα θυμάμαι 1900-1969, vol. 1, Kedros, Athens 1981, p. 49.

[51] Makris, ‘Οι κήρυκες της ιδέας του έθνους,’ pp. 166-268, 321-343, 531-543, 553-597, 683-694, 733-750.

[52] Martin Crotty, Neil J. Diamant and Mark Edele, The Politics of Veteran Benefits in the Twentieth Century. A Comparative History, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, ΝΥ and London 2020, p. 170.

[53] Makris, ‘Οι κήρυκες της ιδέας του έθνους,’ pp. 941-945. For the theoretical context see Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery, Metropolitan Books, New York 2004; John Horne, ‘The living’ in Jay Winter (ed.), The Cambridge History of the First World War, vol. III, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2014, pp. 612-616.

[54] Makris, ‘Οι κήρυκες της ιδέας του έθνους,’ pp. 344-492.

[55] Ibid., pp. 910-912, 918-919, 945-946.

[56] For example see Vasilios Gennimatas, ‘Το τελευταίον έτος εις Μ. Ασίαν,’ Macedonia (25 May 1930); Spanomanolis, Αιχμάλωτοι των Τούρκων, p. 209; Konstantinos Ntampos, Μικρά Ασία 1914-1922. Το χρονολόγιο του ανθυπασπιστή Κωνσταντίνου Ντάμπου, Giannis Makridakis (ed.), Pelinnaio, Chios 2005, p. 46.

[57] See CAMS, MA, n. 286, Konstantinos Demiris, ‘Αναμνήσεις από το Οδεμήσι’ (1966), p. 9; n. 370, Athanasios Loumos, ‘Οπισθοχώρησις του Γ΄ Σώματος Στρατού’ (1933), p. 1; n. 519, Dimitrios Simvonis, ‘Αυτοβιογραφία’ (1970), p. 13; Christoforos Naltsas, ‘Η εκστρατεία της Μ. Ασίας,’ Macedonia (11-12 April 1930); Tsaprazlis, Απ’ τη Δομνίστα, p. 77; Karagiannis, Το ημερολόγιον, pp. 341, 364; Apostolidis, Όσα θυμάμαι, p. 229; Ntampos, Μικρά Ασία, pp. 26-27.

[58] CAMS, MA, n. 170, Ioannis Papadopoulos, ‘Αυτοβιογραφία’ (1961), pp. 68-69, 72, 84-86; Karagiannis, Το ημερολόγιον, pp. 138, 297; Apostolidis, Όσα θυμάμαι, pp.19-21; Giorgis Exarchos (ed.), Ενθύμιον Στρατού, Ermis-Kronos, [Athens] 1987, pp. 45-46.

[59] Philippos Orfanos [Pantelis Pouliopoulos], Πόλεμος κατά του Πολέμου. Αποφάσεις του Πρώτου Πανελληνίου Συνεδρίου Παλαιών Πολεμιστών και Θυμάτων Στρατού, Diethnis Vivliothiki, Athens 2008 (1st ed. 1924), pp. 28-30; P. Nikas, Το βιβλίο του φαντάρου, Alexandria 1925, p. 22. See various articles in Rizospastis during the interwar period (e.g. 28 August 1928, 27 July 1933, 13-14 August 1933).

[60] Apostolidis, Όσα θυμάμαι, p. 228; To Vima (12 November 1978).

[61] Tonia Kafetzaki, Προσφυγιά και λογοτεχνία. Εικόνες του Μικρασιάτη πρόσφυγα στη μεσοπολεμική πεζογραφία, Poreia, Athens 2003, pp. 27-29.

[62] Stratis Myrivilis, Η δασκάλα με τα χρυσά μάτια, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 2018. The novel was originally published in I Kathimerini in 1931-1932 and as a book in 1933.

[63] Ibid., pp. 15, 136.

[64] Ibid., pp. 132-136.

[65] Bruno Cabanes, The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2014, pp. 300-313.

[66] Myrivilis, Η δασκάλα, pp. 250-259.

[67] Thanasis Petsalis-Diomidis, Δεκατρία χρόνια, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 1977, p. 250; I.M. Panagiotopoulos, Αστροφεγγιά. Η ιστορία μιας εφηβείας, Astir, Athens 1980, pp. 5, 160; Giorgos Theotokas, Αργώ, Vivliopoleion tis Estias, Athens 2016, pp. 207-208.

[68] See Stefanos Morfis, ‘Αιχμαλώτων γυρισμός,’ Noumas 774 (May 1923), p. 329; G. Athanas [Georgios Athanasiadis-Novas], Καιρός πολέμου, Sideris, Athens [1924], pp. 56-60; Maria Zampa, Τα τραγούδια μου, Athens 1924, p. 10; Markos Tsirimokos, Ώρες του δειλινού, Athens 1930, p. 24. For Sikelianos’ poem see Ανθολογία της νεοελληνικής γραμματείας. Η ποίηση, vol. III, Iraklis, Renos, Irkos and Stantis Apostolidis (ed.), Ta Nea Ellinika, Athens 2011, pp. 1346-1347.

[69] See the issues of April and May 1924.

[70] Kafetzaki, Προσφυγιά και λογοτεχνία, p. 95.

Dimitris Kamouzis is a Researcher at the Centre for Asia Minor Studies (Athens, Greece). He studied at the University of Cyprus and the University of Birmingham and completed his PhD in History at the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, King’s College London. He has been a scholar of the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation, a Research Fellow of the John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation and the National & Kapodistrian University of Athens and a Teaching Fellow at King’s College London. He has participated in numerous conferences and has published several journal articles and book chapters. His latest book is entitled Greeks in Turkey: Elite Nationalism and Minority Politics in Late Ottoman and Early Republican Istanbul (Oxon & New York: SOAS/Routledge Studies on the Middle East, 2021). Research interests: Modern Greek History, Greek-Turkish Relations, Non-Muslim Minorities in the Ottoman Empire/Turkey, Oral History, Refugee Studies and the History of Humanitarianism.

Dimitris Kamouzis is a Researcher at the Centre for Asia Minor Studies (Athens, Greece). He studied at the University of Cyprus and the University of Birmingham and completed his PhD in History at the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, King’s College London. He has been a scholar of the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation, a Research Fellow of the John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation and the National & Kapodistrian University of Athens and a Teaching Fellow at King’s College London. He has participated in numerous conferences and has published several journal articles and book chapters. His latest book is entitled Greeks in Turkey: Elite Nationalism and Minority Politics in Late Ottoman and Early Republican Istanbul (Oxon & New York: SOAS/Routledge Studies on the Middle East, 2021). Research interests: Modern Greek History, Greek-Turkish Relations, Non-Muslim Minorities in the Ottoman Empire/Turkey, Oral History, Refugee Studies and the History of Humanitarianism.

Charalampos Minasidis is a PhD candidate in the History Department at The University of Texas at Austin. His dissertation entitled War is the Father of All: Citizen Soldiers, Mobilizations and Democratization in the Kingdom of Greece and the Ottoman Empire during the Early 20th Century examines the human landscape of total mobilization via the social category of citizen soldiers as a way to study Greek and Ottoman society at war during the early 20th century. He holds an MA in The History of Warfare (2008) from King’s College London and an MA in Balkan and Turkish History (2013), a BA in Political Sciences (2014) and a BA in History (2007) from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. He has conducted several research projects at the Society for Macedonian Studies and collaborates with projects, such as the 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War et al. He is the author of Η Πολιτική των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών στο Μακεδονικό Ζήτημα τη Δεκαετία του 1940 [United States Policy on the Macedonian Question during the 1940s] (2016).

Alexandros Makris completed his PhD in History at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (thesis title: «’The preachers of the idea of the nation’ Veterans and War Victims in Greece (1912–1940)», 2021). He received a scholarship from the Greek State Scholarship Foundation for his doctoral studies (2018–2020). He completed his studies in Political Science and History at the Panteion University of Athens (2014) and he holds a Master of Science in Modern History from the same university (2017). He is the author of the book chapter ‘“War against war”: The antimilitarist activities of Greek veterans (1922–1925)’ in the volume The role of the military in peacebuilding, (under publication by Bloomsbury Academics). He has participated in conferences in Greece and abroad. He worked at the Society of Study of the Greek Left Youth (EMIAN), the ‘Hestia’ Publishers, the Hellenic History Foundation (IDISME) and the ‘Beyond Borders’ International Documentary Festival.