Συνοπτική Περιγραφή της Έρευνας

Υπάρχουν σχεδόν 50.000 αρχειακά έγγραφα που σχετίζονται με την Ελληνική Επανάσταση στα Οθωμανικά Κρατικά Αρχεία στην Κωνσταντινούπολη, ωστόσο οι επιστημονικές έρευνες με βάση αυτές τις πηγές παραμένουν εξαιρετικά περιορισμένες. Σε όλα αυτά τα έγγραφα, οι προσπάθειες της Υψηλής Πύλης για την κινητοποίηση των μουσουλμάνων Αλβανών επαρχιακών προκρίτων-πολεμάρχων εναντίον των Ελλήνων ανταρτών ξεχωρίζουν ως κεντρικό θέμα. Έχοντας εξαντλήσει τις πηγές στρατιωτικού δυναμικού στον αγώνα του με τους επαρχιακούς προκρίτους (αγιάνηδες) κατά τη δεκαετία πριν από την Ελληνική Επανάσταση, το οθωμανικό κράτος ήταν κυριολεκτικά στο έλεος των Αλβανών πολέμαρχων και μισθοφόρων για την καταστολή της ελληνικής επανάστασης, μέχρι την εμφάνιση των Αιγυπτιακών δυνάμεων το 1825. Ωστόσο, οι Αλβανοί ακολούθησαν τα δικά τους ένστικτα επιβίωσης και τις επιδιώξεις τους και η αποστροφή τους στο να προβάλουν ένα ενωμένο μουσουλμανικό μέτωπο εναντίον των Ελλήνων αποδείχτηκε μια ακόμα αποτυχία του ήδη χρεοκοπημένου συστήματος αυτοκρατορικής αφοσίωσης της Υψηλής Πύλης. Υπάρχουν αναρίθμητα έγγραφα στα οποία οι Οθωμανοί διοικητές αξιολογούν την αλβανική αντίδραση ως το κύριο εμπόδιο στην καταστολή της ελληνικής εξέγερσης. Η απροθυμία των ιστορικών να αποδώσουν στους Αλβανούς των αρχών του 19ου αιώνα τις ιδιότητες ενός λαού ικανού να επιδιώξει τα δικά του συμφέροντα –σε αντιδιαστολή με το να αποτελούν απλή συσσωμάτωση μισθοφορικών φυλών– εμπόδισε σε μεγάλο βαθμό την σαφή κατανόηση του βασικού ρόλου τους στην Ελληνική Επανάσταση.

Η προτεινόμενη έρευνα θα διερευνήσει τους τρόπους με τους οποίους οι συντελεστές της μετά-Τεπελενλί τάξης διαμόρφωσαν την πορεία της Ελληνικής Επανάστασης, δίνοντας ιδιαίτερη έμφαση στο μουσουλμανικό αλβανικό στοιχείο. Κάνοντας εκτεταμένη χρήση του οθωμανικού αρχειακού υλικού, η έρευνα θα ακολουθήσει τη σταδιοδρομία των έκπληκτων Αλβανών πολέμαρχων που προσπαθούσαν να βρουν τη θέση τους ανάμεσα στους Έλληνες επαναστάτες που έκαναν αγώνα για ανεξαρτησία και τους πράκτορες της Υψηλής Πύλης που προσπαθούσαν να αποκαταστήσουν την αυτοκρατορική εξουσία.

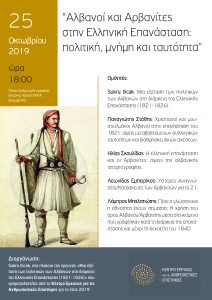

Ημερίδα

«Αλβανοί και Αρβανίτες στην Ελληνική Επανάσταση: πολιτική, μνήμη και ταυτότητα»

Ιστορικό Αρχείο ΕΚΠΑ

(Σκουφά 45, Κολωνάκι)

Παρασκευή 25 Οκτωβρίου 2019

Η ημερίδα πραγματοποιείται στο πλαίσιο της έρευνας με τίτλο «Μια εξέταση των πολιτικών των Αλβανών στη διάρκεια της Ελληνικής Επανάστασης (1821-1826)» η οποία χρηματοδοτείται από το Κέντρο Έρευνας για τις Ανθρωπιστικές Επιστήμες (ΚΕΑΕ) για το έτος 2019.

Ομιλητές

Sukru Ilicak: Μια εξέταση των πολιτικών των Αλβανών στη διάρκεια της Ελληνικής Επανάστασης (1821-1826).

Παναγιώτης Στάθης: Χριστιανοί και μουσουλμάνοι Αλβανοί στην επανάσταση του 1821: όψεις μεταβαλλόμενων συλλογικών ταυτοτήτων και διαθρησκευτικών σχέσεων.

Ηλίας Σκουλίδας: Η ελληνική επανάσταση και οι Αρβανίτες: όψεις της αλβανικής ιστοριογραφίας.

Λεωνίδας Εμπειρίκος: Ύστερες Αναγνώσεις/ Κατασκευές των Αρβανιτών για το 21.

Λάμπρος Μπαλτσιώτης: Πότε η γλώσσα και η εθνότητα έχουν σημασία; Η χρήση του όρου Αλβανός/ Αρβανίτης μέσα στα κείμενα που γράφτηκαν κατά τη διάρκεια της επανάστασης και μέχρι τη δεκαετία του 1840.

Research: “An Examination of Muslim Albanian Politics during the Greek Revolution (1821-1826)”

Researcher: Dr. Şükrü Ilıcak

The research project “An Examination of Muslim Albanian Politics during the Greek Revolution (1821-1826)” was funded by the Research Centre for the Humanities (RCH) for the year 2019.

A theme that stands out in all the documents produced by the Ottoman state throughout the Greek War of Independence is the Sublime Porte’s unsuccessful efforts to mobilize Muslim Albanian magnates-cum-warlords to fight its battles against the Greek insurgents. The multitude of documents is due to the fact that the Ottoman state had essentially no army, nor much means to raise one in the wake of the revolution. Strongly reminiscent of the circumstances attending the dissolution of several ancient empires, the Sublime Porte was obliged to resort to the “violence market,” whose most important providers were Muslim Albanian warlords. The Ottoman state was literally at their mercy for the suppression of the Greek uprising until the advent of the Egyptian forces in 1825.

This is an unknown aspect in the historiography of the Greek War of Independence because most students of the period tend to downplay the role of the Albanian element. One way to achieve this is to treat Muslim Albanians as Turks—either by naming them turkalvanoi or completely ignoring their Albanian identity—and Christian Albanians as Greeks, reducing the events to a tug-of-war between two ostensible sides. The picture is much more complicated though. On the field, the Greek War of Independence was a power struggle among a multitude of players with incessant realignment of interests and redistribution of power.

The reasons behind the adverse circumstances of the Ottoman armed forces and why Albanians played such an important role in the Greek War of Independence lie in the preceding decade, which constitutes one of the most understudied periods of Ottoman history. The Treaty of Bucharest (May 1812) and Russia’s revised nonaggressive imperial agenda in the post-Napoleonic world order brought about the favorable conditions for a certain clique at the Sublime Porte to deal with its internal affairs and eliminate the provincial magnates (ayans), without whose support the Ottoman central state could not raise an army or taxes since the Russo-Ottoman war of 1768-74. The ayans had carved out almost autonomous statelets for themselves and especially during the Russian war of 1806-12, they became ever more independent and less responsive to the Sublime Porte’s demands. Hence, in February 1813, the Sublime Porte officially announced and embarked upon a military and administrative project to reassert itself in the provinces. What followed was, to all intents and purposes, a civil war between the Ottoman central state and a myriad of provincial magnates of varying calibers, religions, ethnicities and levels of popular support. Official Ottoman documents and chronicles allow us to trace dozens of urban and rural uprisings led by provincial magnates throughout the empire against the Sublime Porte’s encroachments.

As a result of this de-ayanization process, in a decade, large sections of the empire were ruined and the Sublime Porte exhausted its pool of military manpower. Provincial magnates were toppled hastily without replacing their networks and infrastructures with effective alternatives. Consequently, the imperial viziers who replaced the magnates found it extremely difficult to recruit and mobilize soldiers and were obliged to hire mercenaries when the Greek Revolution broke out.

The most crucial stage of the de-ayanization was the suppression of the legendary Tosk Albanian Mutasarrıf of Ioannina, Ali Pasha of Tepeleni. The Sublime Porte succeeded in eliminating Ali Pasha after one and a half years of serious strife and almost a year into the Greek Revolution. The pashaliks of Ioannina, Vlorë (Gr. Αυλώνας) and Delvinë (Gr. Δέλβινο), namely a great part of Toskëria, were united under the governorship of Ömer Vrioni, Ali Pasha’s treasurer, who had defected to the Sublime Porte in a timely manner before his master’s demise.

In most of the Tosk lands, the real power remained in the hands of a party of disgruntled strongmen of Ali Pasha’s court. Being the insurgent Greeks’ immediate neighbors and still controlling the most operational military man-power in the region after the disintegration of Ali Pasha’s government, their stand against the Greek Revolution was of make-or-break importance. The members of this Tosk military oligarchy—such as Ali Pasha’s sword-bearer (Turk. silahdar) Ilyas Poda, seal-keeper (Turk. mühürdar) Ago Vasiari, treasurer (Turk. hazinedar) Ömer Vrioni and his nephews Ahmed and Hasan Vrioni, chief of guards (Turk. bölükbaşı) Tahir Abbas, chief orderly (Turk. kapuçukadar) Elmas Mecho, and military chiefs such as Dervish Hasan and Sulcho Gorcha (Süleyman Agha)—were Ali Pasha’s creatures. According to William Meyer, the British consul at Preveza and an extremely well-informed, erudite and intuitive observer of Albanian politics, the members of this “Tosk League” were a new race of individuals who Ali Pasha has selected from the lowest classes to replace the principal and powerful Albanian families, and who have been made the instruments of his dark proceedings.

Despite the fact that most of his officers had abandoned Ali Pasha and joined the Ottoman army at its first approach in August 1820, due to the imperial viziers’ incompetence and sluggishness during the siege of Ioannina and gross misconduct and extortionary practices in the region, they signed formal pacts with the Greek revolutionaries in September 1820 through the mediation of Odysseas Androutsos and, in Meyer’s words, became “confederates.” Meyer’s reports provide the most prolific testimony of how each failed attempt of the Ottoman army to capture Ali Pasha resulted in the enhancement of the understanding between the Tosk warlords and Greek revolutionaries. The locals’ disgust with the imperial viziers was a common theme of the de-ayanization period and Albanian lands were no exception to the pattern. While Ali Pasha held out against the siege, his comrades in arms were in open cooperation with the Greek insurgents. By the end of 1821, the strife had assumed “the character of a national war of the united Albanian and Greek people against the Musselman [i.e. Ottoman] arms.”

As early as the spring of 1822, it had become evident to all parties that the Greek uprising would not be quelled unless the Albanians effectively cooperated with the Sublime Porte. And the Albanians acted on this principal and confidence throughout the Greek Revolution. Thus, in the following years, the cornerstone of the Tosk League’s policy was twofold: First, as regards the Ottoman state—while they were still very bitter about the downfall of Ali Pasha and extremely distrustful of the state—they did everything in their power to paralyze the Sublime Porte’s operations to establish its authority in their lands. Moreover, the Sublime Porte’s strife with the Greeks presented them an opportunity to enrich themselves by absorbing the Ottoman fisc through mercenary salaries. Hence, the longer they protracted the strife the richer they got. Second, as regards the Greeks, although they harbored “strong feelings of jealousy and mistrust as to the ultimate views of the Greek nation,” they had no ground of hostility against the Greek insurgents and were truly disaffected to the cause of the Ottoman state. “The policy of the Albanians therefore during the actual contest of the Greeks with the Porte, though not avowed, was in fact that of an armed neutrality, secretly counteracting the Turks when they were likely to gain the ascendant, and checking the Greeks when they were inclined to encroach upon the Albanian interests.”

Temporizing and evading as far as possible the execution of orders were the most essential qualities of the Albanian “armed neutrality” policy. Despite the Sublime Porte’s reiterated exhortations, Tosk mercenaries were often tardy in taking the field and obeying orders; even when they followed through, they were reluctant to fight against the Greeks. Ottoman army encampments and castles in and around the Morea were in a state of continuous unrest and trouble on the pretext of delayed salaries or provisions. When Albanian mercenaries faced hardship, they had no scruples about deserting from the camps, surrendering the castles entrusted to their protection or leaving the positions seized after considerable sacrifice, allowing the Greeks to break sieges, lifting sieges or deserting from the army on the pretext of bad weather.

The understanding between the Tosk military oligarchy and Greek insurgents constituted a major obstacle for the Sublime Porte to the suppression of the Greek War of Independence. Meyer’s reports are in agreement with those of the Ottoman administrators that the Greek uprising could have been quelled at its outset had these Tosk warlords desired to do so. Yet, historians’ reluctance to grant the Albanians of the early 19th century the qualities of a people capable of pursuing its own interests—as opposed to being a mere agglomeration of mercenary tribes—has largely prevented a clear understanding of their key role in the Greek Revolution. Amid the murk of revolutionary turmoil, Albanians were at the very heart of the matter, following their own survival instincts and pursuing their agenda while remaining quite unresponsive to the Sublime Porte’s demands.

Ο Χ. Σουκρού Ιλιτζάκ γεννήθηκε και μεγάλωσε στην Άγκυρα. Ακολουθώντας τα χνάρια του ρεμπέτικου, άρχισε να αναπτύσσει ένα σοβαρό ενδιαφέρον για την Ελλάδα όταν ήταν στο πανεπιστήμιο. Αποφάσισε να κάνει ακαδημαϊκή καριέρα και να ειδικευτεί στα λεγόμενα «τρία έθνη» της οθωμανικής αυτοκρατορίας, δηλαδή τους Έλληνες, τους Αρμενίους και τους Εβραίους. Συνέχισε τις σπουδές του στην Τουρκία, την Ελλάδα και τις Η.Π.Α. Αναγορεύτηκε διδάκτορας του Πανεπιστημίου Χάρβαρντ το 2011, με τίτλο διατριβής “A Radical Rethinking of Empire: Ottoman State and Society during the Greek War of Independence (1821-1826) [Μία ριζοσπαστική αναθεώρηση της Αυτοκρατορίας: Οθωμανικό κράτος και κοινωνία στη διάρκεια της Ελληνικής Επανάστασης]”. Η διατριβή του εξετάζει την Ελληνική Επανάσταση ως μία οθωμανική εμπειρία, εξερευνώντας συγκεκριμένα πώς ο Σουλτάνος Μαχμούτ ο Β΄ (1808-1839) και η κεντρική κρατική ελίτ προσπάθησαν να την εξηγήσουν και να αντιδράσουν στον ταχύτατα μεταβαλλόμενο κόσμο γύρω τους.

- “Revolutionary Athens through Ottoman Eyes (1821-1828)” in Maria Georgopoulou (ed.), Ottoman Athens (Athens: Aikaterini Laskaridi Foundation, forthcoming in 2019).

- “Greek War of Independence and the Demise of the Janissary Complex: A New Interpretation of the Auspicious Incident” in Marinos Sariyannis (ed.) Political Thought and Practice in the Ottoman Empire (Halcyon Days in Crete IX Symposium). Ed. (Rethymno: Crete University Press, forthcoming in 2019.

- “Το να είσαι Τούρκος στην Ελλάδα” in Iraklis Millas (ed.) Η «Νέα» Τουρκία εκ των έσω, (Sideris, forthcoming in 2019).

- “Το συναπάντημα του Τούρκου με την γενοκτονία,” Σύγχρονα Θέματα: 142 (2018).

- “My Dear Son Garabed. I Read Your Letter. I Cried, I Laughed.” Kojaian Family Letters from Efkere to America, 1912-1919 (Istanbul: Histor Press, 2018).

- “H οθωμανική πολιτική φιλοσοφία και η αντίδραση στην ελληνική «αταξία»” [Ottoman Political Philosophy and Reactions towards the Greek “Sedition”], in Tanos Veremis (ed.), 1821: Η γέννηση ενός έθνους–κράτους [1821, the Birth of a Nation-State], vol. 5. (Athens: Skai Books, 2010).

- “The Revolt of Alexandros Ipsilantis and the Fate of the Fanariots in Ottoman Documents” in Petros Pizanias (ed.), Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση του 1821: ένα ευρωπαϊκό γεγονός (Athens: Kedros, 2009).

- “Unknown ‘Freedom’ Tales of Ottoman Greeks” in Bahattin Öztuncay (ed.), 100th Anniversary of the Restoration of the Constitution (Istanbul: Sadberk Hanım Museum, 2008).

- Kendi Kendine Ermenice [Teach Yourself Armenian] (Istanbul: The Armenian Patriarchate, 2006) (with Rachel Goshgarian).

- Έλληνες και Εβραίοι Εργάτες στη Θεσσαλονίκη των Νεότουρκων [Greek and Jewish Workers in Young Turk Salonica]. (Ioannina: Isnafi, 2004).

- “Jewish Socialism in Ottoman Salonica,” Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 2:2 (2002).

- “Kökenbilim ve Tarih Bilinci [Etymology and Historical Consciousness]” Bilim ve Ütopya, July 1993.

- “Entelektüel Cambazlık [Intellectual Acrobatics]” Tarih ve Toplum, August 1993.